Abstract

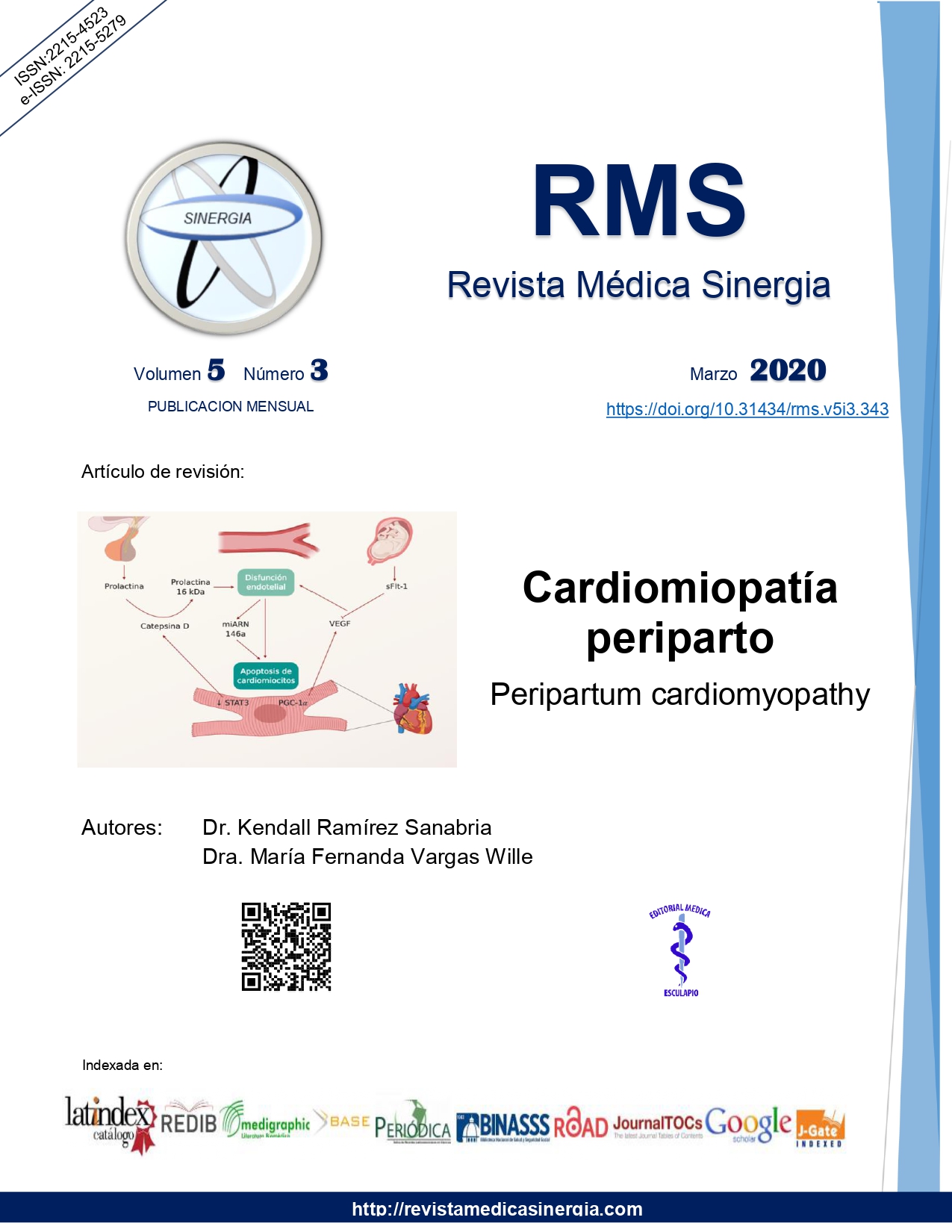

Peripartum cardiomyopathy consists of cardiomyopathy with associated systolic dysfunction occurring in the pregnant woman near term or in the first few weeks postpartum. Risk factors for CPP include African ancestry, pregnancy associated hypertensive disorders such as preeclampsia, advanced maternal age (over 30 years old) and multiple gestation pregnancy. Various physiopathological mechanisms have been proposed to be causative, such as a rise in prolactin levels, lowered antioxidant transcription factors, e.g. STAT3, and a rise in placental originated proteins like sFlt-1, which together produce endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes. CPP is a diagnosis of exclusion; for women in the peripartum period who present with heart failure symptoms other causes must be excluded, including preexistent dilated or valvular cardiomyopathy, acute myocardial infarction and pulmonary thromboembolism. Currently management is based on the basic treatment for heart failure and hemodynamic support in patients that require it.

References

Cunningham FC, Byrne JJ, Nelson DB. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 133:167-79. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003011.

Arany Z, Elkayam U. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2016; 133:1397-1409. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020491.

Honigberg MC, Givertz M. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. BJM. 2019; 364:k5287. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k5287.

Sliwa K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Petrie MC, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur J of Heart Failure. 2010; 12:767-778. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfq120.

Koenig T, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Bauersachs J. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Herz. 2018; 43: 431-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-018-4709-z.

Karaye KM, et al. Serum Selenium and ceruloplasmin in nigerians with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2015; 16(4): 7644-54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16047644.

Main EK, McCain CL, Morton CH, Holtby S, Lawton ES. Pregnancy-related mortality in California: causes, characteristics, and improvement opportunities. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:938-47. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000746.

Sliwa K, Mebazaa A, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients from the worldwide registry on peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM). Eur J of Heart Failure. 2017; 19:1131-41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.780.

Afana M, Brinkikji W, Kao D, et al. Characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of peripartum cardiomyopathy diagnosed during delivery in the United States from The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Database. J Card Fail. 2016; 22:512-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.02.008.

Schelbert EB, Elkayam U, Cooper LT, et al. Myocardial damage detected by late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance is uncommon in peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017; 6:e005472. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.005472.

Harhous Z, Booz G, Ovize M, Bidaux G, Kurdi M. An update on the multifaceted roles of STAT3 in the heart. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019; 6:1-18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2019.00150.

Naftali-Shani N, et al. Modeling peripartum cardiomyopathy with human induced pluripotent stem cells reveals distinctive abnormal function of cardiomyocytes. Circulation. 2018; 138:2721-23. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035950.

Ware JS, Li J, Mazaika E, et al. Shared genetic predisposition in peripartum and dilated cardiomyopathies. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:233-41. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1505517.

Honigberg MC, Givertz MM. Arrhythmias in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2015; 7:309-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccep.2015.03.010.

Bauersachs J, Arrigo M, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, et al. Current management of patients with severe acute peripartum cardiomyopathy: a practical guidance from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Study Group on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18:1096-1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.586.

Elkayam U, Goland S, Pieper PG, Silverside CK. High-risk cardiac disease in pregnancy: part I. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68:396-410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.048.

Ntusi NB, Badri M, Gumedze F, Sliwa K, Mayosi BM. Pregnancy-associated heart failure: a comparison of clinical presentation and outcome between hypertensive heart failure of pregnancy and idiopathic peripartum cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0133466. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133466.

Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Haghikia A, Nonhoff J, Bauersachs J. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: current management and future perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2015; 36(18): 1090-97. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv009.

Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Haghikia A, Berliner D, et al. Bromocriptine for the treatment of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a multicentre randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2017; 38:2671-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx355.

Arrigo M, Blet A, Mebazaa A. Bromocriptine for the treatment of peripartum cardiomyopathy: welcome on BOARD. European Heart Journal, 38(35), 2680-2682. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx428.

Nonhoff J, Ricke-Hoch M, Mueller M, et al. Serelaxin treatment promotes adaptive hypertrophy but does not prevent heart failure in experimental peripartum cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Resc. 2017; 113:598-608. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvw245.